Agriculture at Rokeby, by Winty Aldrich

It is believed that during the epoch before 1609, some of the fields at Rokeby were kept open by periodic burning and were planted in maize, beans and squash by the Lenni Lenape. Not long after the land was granted by the Crown to Colonel Pieter Schuyler of Albany in 1688 it became part of the holdings of Colonel Henry Beekman. Beginning in 1712 Beekman subdivided his lands into 150 acre parcels and leased them to German Palatine settlers who were emigrating to Germantown. These durable leaseholds typically ran for three generations and obliged the tenant to pay rent of a few shillings a year, a “fat hen,” a couple of bushels of “good merchantable winter wheat,” and a day’s labor on common roads. It was these folk -- in our case the Benners, Finehouts, Sipperlys, Fellers and Mohrs -- who cleared the land, apportioned it into cropland, pasturage and woodlots, made boundary walls with stones dragged from fields, and generally created the pastoral landscape that we know today. Wells were dug, houses and barns built, lanes made. Wheat was the principal cash crop until the early 19th century -- ground in the landlord’s mill and shipped in his sloops to market in New York.

The ownership passed to Beekman’s daughter Margaret Livingston and then to her daughter Alida. In 1811, upon the return from Paris of Alida and her husband General John Armstrong, it was decided to buy out the surviving leaseholds on five adjoining farms and consolidate them into one 750 acre farm -- “La Bergerie,” the sheep-fold. The main house, farmhouse and barns were built and a Merino sheep farm established, the original animals a gift from the Emperor Napoleon. It was a breed first introduced to America several years earlier by Alida’s brother, Chancellor Livingston. Armstrong was a committed agriculturalist and experimented with fruit raising and various forms of animal husbandry. This experience is documented in his published treatise on agriculture, which appeared in at least three editions.

The sheep did not long continue here, the property’s name was changed to Rokeby, and in 1835 it passed to Armstrong’s son-in-law William B. Astor. For the next 65 years the owners took much less direct interest in farming. Instead, they carried out ornamental landscape schemes and plantings while a tenant farmer, Philip Hainer, operated the farm, followed by Charles House as the employed manger after Astor’s death in 1875. During this period it is unclear what crops were produced or herds maintained. The two constituent southerly parcels were conveyed to relatives, while Astor’s great-grandchildren, the Chanlers, inherited Rokeby’s remaining 450 acres.

In 1899 Margaret Livingston Chanler (later Aldrich) became the sole owner and determined to resume active farm operations. Selecting dairy -- which, with fruit growing, had become the region’s dominant farm type in the latter 19th century -- she established a “certified milk farm” under provisions of a state law that certified the clean handling and processing of milk if the producer scrupulously adhered to certain elaborate precautions. Hence silos, concrete barns, water systems, an ice-house and refrigeration, a creamery/bottling building (at a specified distance removed from the cows), laundered white uniforms and caps for the staff, and a herd of pedigreed Jersey cows all materialized. The operation was subject to constant inspections, but the milk commanded a premium price in New York City where mothers weaning their babies could be certain that the infants would be safe from undulant fever and other threats.

Within a few years more advanced state laws were enacted requiring pasteurization and the costly certified dairy operation was given up. In the 1920’s Charles House was succeeded by John Milton Risley as superintendent, a Cornell-educated dairy manager formerly employed by Governor Morton’s huge model farm at Rhinecliff. Risley died in 1956, and Rokeby Dairy Farm sold its herd and shut down in 1961. During its last several decades the farm boasted about 60 milking Holsteins, with an appropriate number of heifers in waiting. The milk was taken daily in 10-gallon cans to a depot in Red Hook where it was collected by Borden’s (paying 6 cents a quart) for processing and distribution. Fields were treated with cow manure, lime, and phosphate as needed, and planted in rotation with field corn, oats, alfalfa, timothy. Hay was baled and barn-stored; corn on the stalk was reduced to ensilage and silo-stored. A team of draft horses, a small Farmall tractor and an International caterpillar tractor did the pulling. There was also a small orchard on Rokeby Road, a vegetable and flower garden and greenhouse operation, and some pigs and chickens, all for home use. Since 1961 corn and hay have been cultivated for sale from time to time. In the 1970’s Rokeby was designated under the State’s Agricultural District Law.

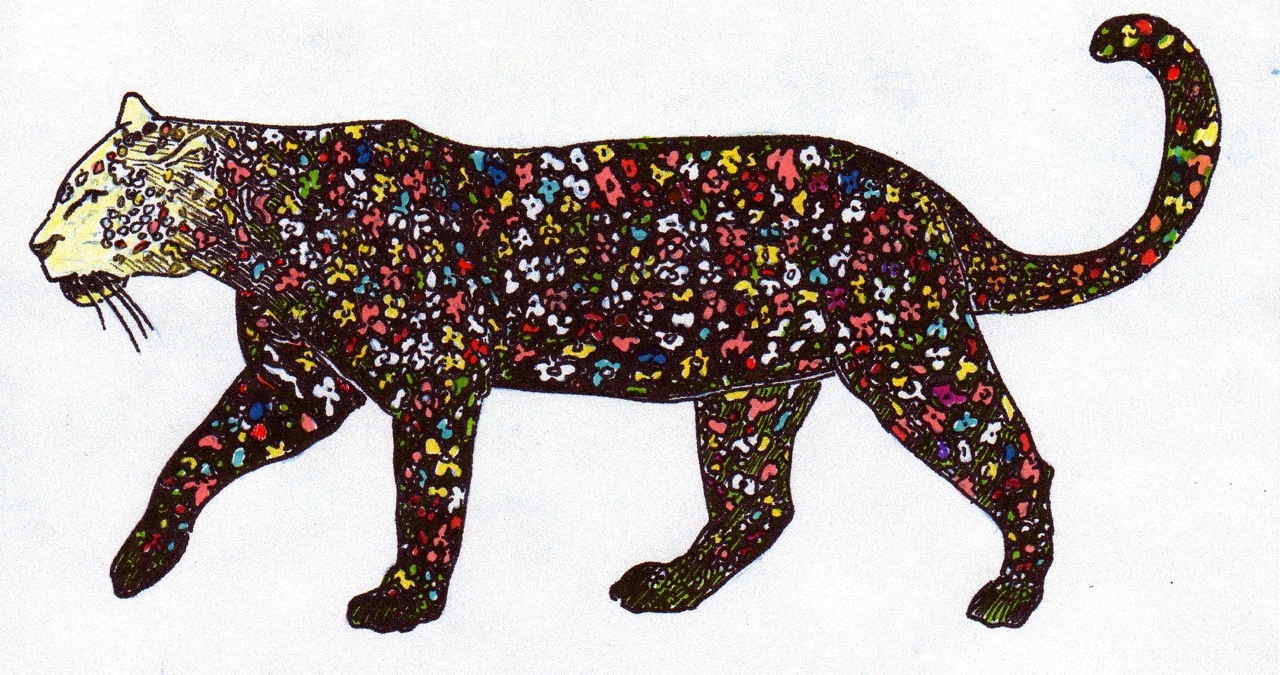

Alida Kahn is Alida Livingston's great great great great great granddaughter, and possibly a Future Flower Farmer of America.